This chapter examines five important fusion albums. With the exception of Bagels and Bongos which is presented first, they are in chronological order. Bagels and Bongos. is a bridge album between the majority of the Yiddish fusion albums produced in the 1950s and 1960s and the musical standouts that are explained in this study.

Each album’s case study is divided into three sections. The first section has background into the individual album, including available recording history, and reviews. The second section of each case study examines a number of individual tracks in the style of Gunther Schuller. The last section of each case study is a conclusion.

Appendix A has a sampling of some of the other albums that could have been included in this study with pictures of their covers and descriptions of the albums. Musically some of them are very interesting, and have wonderful musicians on them (see Mazel Tov, Mis Amigos). Some are musically interesting, though the musicians who created the music are lost to history (see Raisins and Almonds Cha Cha Cha and Merengues), while others make one think, “do we really need a Jewish-themed parody of a band that is already made up of mostly Jews (see Al Tijuana and His Jewish Brass)”? Lastly there are the albums that are trying to make popular dance fads acceptable to older generations, such as the “twist” albums (see Bei Mir “Twist” Du Schön and Twistin The Freilach).

Bagels and Bongos

Irving Fields’ Bagels and Bongos, when listened to today sounds dated, though of the albums under study was the only one where the same artist recorded a follow up album.

Figure 1: Irving Fields Trio - “Bagels and Bongos” (cover)

Figure 2: Irving Fields Trio -“More Bagels and Bongos” (cover)

Irving Fields has been accused of being too commercial over the years. Here is what another musician in this study, Terry Gibbs, had to say about him in his autobiography:

There was a cocktail piano player around New York who wrote a famous song called “Miami [Beach] Rhumba.” His name wasn't familiar to most people, but amongst musicians, if you said Irving Fields, they would break up laughing. Tiny [Kahn], who always had a great sense of humor, once wrote a song called, “Welcome Home, Irving, from Langley Field,” and then wrote a sequel to that called “Welcome Home, Langley, from Irving Fields.”

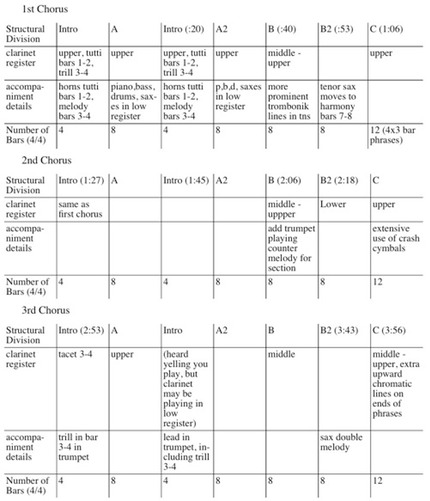

For jazz musicians, the commercial part of Fields’ work was even more evident in his playing style than in his composition. One of the hallmarks of Fields’ playing style is the supremacy of the melody. No matter what underlying rhythms he uses the melody will always be clear. Fields’ primary music interest was in exploring different rhythms.

Irving Fields could play every style and tune that the consumer wanted. The Latin music was just the ritornello of his ventures that is remembered. Bagels and Bongos came out of a idea Fields had while working in Boston, and a couple different versions of the story are told. In one version, after hearing a Jewish radio program on the air the day before, he tells his drummer to play a rumba, and over this he played “Raisins and Almonds.” It worked: the Jewish tam (feeling) was still there and at the same time it was danceable. The second story is that someone in the audience starting dancing a rumba to a Jewish tune that Fields was playing as a fox trot. Fields changed the tune to a rumba and more people got up and danced.

No matter which story is true, the album that resulted from the Jewish and rhumba inspiration was recorded as an experiment at Ace Studios in Boston and the tapes brought down to Milt Gabler at Decca. The resulting album sold two million copies (according to Reboot Stereophonic) when it was released in 1959. It went on to spawn a number of follow up releases, including More Bagels and Bongos, Pizza and Bongos (Italian music), Champagne and Bongos (French music) and Bikinis and Bongos (Hawaiian music). Other artists were also inspired and albums such as Sy Menchin's My Bubba and Zaydes Cha Cha, and Juan Calle and His Latin Lantzmaen’s Mazel Tov Mis Amigos where the result. Personnel listed on the reissue of Bagels and Bongos are: Irving Fields, Piano; Bruno, drums; Henry Seinck, bass; Henry Tapia, bongos.

Bagels and Bongos really is a solo piano album, played over a rhythm section. The arrangements are very straight-ahead and simple. Musically this is the weakest album analyzed in this study. Where the other albums in this study work on a macro scale, Bagels and Bongos is much more interesting on the micro scale of how Irving Fields is embellishing the melody. Bagels and Bongos is a formulaic album, and to our ears today sounds very repetitive.

I Love You Much Too Much (Raye/Towber/Olshanetsky) Quarter note = 120

“Ikh Hob Dikh Tsu Fil Lieb” (Chaim Towber - Alexander Olshanetsky) was a very popular Yiddish theatre love song, and like many of the tracks on the album only the chorus is played. Musically most of the interest lies in how Fields fills in the the longer held notes, as he never wants to leave a spot unfilled. The drums and bongos never stop their groove, but it is just an underlay. Their job is to provide the feeling of being in a night club, with a drink, and the opportunity to dance. The melody is just a nice tune. One can picture the couples dancing slowly around the floor as they hold each other tight hearing the words to the song in their head. The piano part just floats over the steady drums and bongos, creating the sense of longing.

The form of the tune is AABA. The A section is built around a motive that is an eighth note followed by four sixteenths as a pickup to a half note tied to an eighth note.

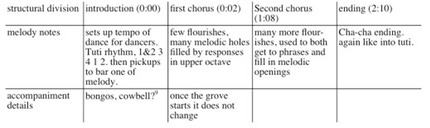

Figure 3: music example from “I Love You Much Too Much”

This examples shows the first two phrases of the A section with the pickup to the third phrase. The B section contrasts with longer phrases. It is played as a Cha-Cha, though the bongos are playing the pattern starting on beat one, rather than beat two.

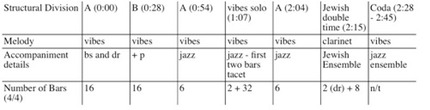

Figure 4: Form Chart “I Love You Much Too Muc

Bagels and Bongos was not the first hybrid Jewish/Latin album to hit the market as many believe. Johnny Conquet's Raisins and Almonds Cha Cha Cha and Merengues was released in 1958. A short overview of Raisins and Almonds Cha Ca Cha can be found in appendix A. And even though Raisins and Almonds Cha Ca Cha has some of the best cover artwork and creative song titles to grace a record, it was nowhere near as popular as Bagels and Bongos.

Lastly, Bagels and Bongos was commercially successful, and is the only album in this study to have a follow-up produced by both the same artist and other artists. Whether it was musically successful is another question. Fifty years later, it is the most dated of the five albums examined here. And while each track works on its own, on the whole it gets repetitive. But, it does show that Latin rhythms and Jewish melodies can be merged successfully into a new fusion music.

Tanz!

Figure 5: “Tanz!” with Dave Tarras and Sam Musiker (cover)

Tanz! was recorded for Epic, Columbia's discount label, at CBS 30th Street Studio, New York City, on September 21-22, 1955. The personel was: Sam Musiker, Dave Tarras (clarinets, leaders); Melvin Solomon (trumpet); Carl Prager, Phil Bodner, Ramon Musiker (reeds); Seymour Megenheimer (accordion); Moe Wechsler (piano); Mack Shopnick (string bass); Irving Gratz (drums); Marty Wilson (Contractor).

Of all the albums in this survey, both the performers and performances on Tanz! stay closest to their roots in Yiddish instrumental music. Nine years after their Savoy session, Dave Tarras and Sammy Musiker returned to the studio to record Tanz! By this time swing was no longer in vogue. And while big band harmonies were still used, the dichotomy between Jewish and jazz was no longer present. The separation of Jewish and jazz elements was necessary on the earlier recordings because the musicians who were not fluent in both musical genres. American born musicians, such as Musiker, were more comfortable merging these two genres.

While the instrumentation on Tanz! is not a full big band, it can be compared to its contemporaries, such as the orchestras lead by Woody Herman and Stan Kenton in transforming dance music to a style for listening. The music on Tanz! is, at its core, all dance music, but played in a style and at tempos more appropriate for the concert hall than the catering hall. Not including the stage shows of Mickey Katz and any incidental use of similar music in Catskill Hotel nightclubs, it would be well over twenty years before this music would be performed in concert halls.

Even though jazz is not explicitly found on Tanz!, it is still present. Rather than showing up as solos on individual tracks, it shows up in the way the album was constructed. Tanz! is a concept album; each side starts with the same tune played by both featured clarinet players. This opening track is then followed by a three part suite featuring one of the clarinetists, answered by two tunes featuring the other clarinetist. The second side ends with a closing tune that features both featured performers. The form of this album can be seen as a call and response in a jazz sense. Though rather than being within an individual song, the call and response is between tracks.

“Sam’s Buglar” offers a more in-depth look into Tanz! This track is the first of two Musiker tracks appearing on side one answering to the Tarras’ suite. One of the jazzier tracks on the album, the arrangement/orchestration of “Sam’s Bulgar” features a number of big band conventions and a swinging eight note.

3. Sam’s Bulgar (Musiker) Featuring Sam Musiker on Clarinet; Quarter note = 147

In his forty-four word line note to the “Sam’s Bulgar,” Ivan Fiedel refrences both Dixeland and Gene Krupa. To paraphrase President Kennedy, it is not what Yiddish music can do for jazz, but what jazz can do for Yiddish music. This is not Sammy Musiker playing one of his father-in-law’s bulgars. He has extended the hybrid nature of the bulgar and brings in swing. Three very traditional Yiddish pick-up notes on the clarinet explode into a 4 bar (4/4) hint at the tune's shout section. This shout section is used before every A section, and to close the tune, but it is not part of the A section.

Figure 6: Form Chart “Sam's Bulgar”

Ivan Fiedel in the original 1956 liner notes to Tanz! describes “Sam’s Bulgar:”

Sam Musiker on Clarinet. We spoke of the contribution of Yiddish Music to jazz. Here Sam shows that the corollary of that is also true. The opening ensemble is a swinging “Bulgar” with shades of Dixeland. Reminds us of Sam’s days with Gene Krupa.

This is not a bulgar written for dancing, rather it is a bulgar written for listening. The intro, which might better be thought of as a ritornello shows its American roots by having a swinging eighth note. However the A section, is quite Jewish, with a close that is vary similar to the close of the A section of “Dem Nayem Sher”. The B section shares a number of motifs with the A section, but is embellished in a more lyrical style. The C section, though, is quite different, starting off with phrases three bars long instead of four. It is made up of two pairs of phrases, and could have been labeled C and C2, though the texture is consistent. While it never loses its Jewish character, the feeling is changed by the fact that in the first phrase of each section the melody starts after the downbeat differentiating it from the A and B sections that start on the downbeat. Having the phrases in the C section be three bars instead of four could just as easily be a Jewish influence as an American one. Many Jewish vocal tunes will jump to the next phrase when one ends, even if they are in the middle of a bar. The drums are also very flashy with plenty of cymbal hits, punching the tune along in a style that is much more American than Jewish.

“Sam’s Bulgar” is not a tune that a bandleader can call for dancing. It is a tune for listening meant for a sophisticated audience that can appreciate the tunes Yiddish origins and big band styling. The chord changes and number of moving background lines can not be heard on the average Yiddish album from the post-war time period.

Looking at one single track cannot show the construction of the through-composed style musical statement that Tanz! was. A very important musical detail is lost on the CD reissue: a pause. The pause to turn over the record is crucial. An idea has been presented on the first side; the Jewish artist has drawn upon all the relevant, contemporary genres: Yiddish theatre, Eastern Europe, American Big Band, and the Middle East. At the end of side one we are presented with a pause, and then a reset as the same opening tune is played to open side two. The pause resets the listeners ear, and sets up the second side to be a look forward at an uplifting future for Yiddish instrumental music. This fact is underscored by the last track being an up-tempo version of one of the most melodramatic ballads in the Yiddish Theatre repertoire, Herman Yablokoff's “Papirosen”.

Tanz! like the Savoy Session before it, is clearly a ‘concept’ album. While Tarras was a draw for modal jazz players, that skill is not featured on this album, as a consequence Tanz! was not able to cross over as a jazz record. Audiences of this time, Jewish and otherwise, were also not at this time used to having any of Yiddish instrumental music as a ‘listening music’. Consumers must have been especially confused when listening to an album whose name translates as ‘dance’. For all these reasons, Tanz! was ahead of its time, and unsurprisingly, did not appear to sell well. Today because of its great playing and continuity Tanz! is seen as among the best, if not the best example of Klezmer music recorded between 1945 and 1975.

Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses

Figure 7: “Mickey Katz plays music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses” (American cover)

Figure 8: “Mickey Katz; Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses” (Israeli cover)

This record was originally released as The Family Danced on a 10 inch LP. In 1955 and 1956 four tracks were added to create Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses. The LP was reissued on CD in 1994 with five additional tracks out of ten recorded in 1964 for a second instrumental album that was never released. The tracks examined here were all included in the 1956 release. They were recorded at six sessions between July 2, 1951, and November 28, 1956. The tracks had been cut over a period of time while Katz was primarily working as a DJ on KABC in Los Angeles and from time to time leading non-Jewish bands in Las Vegas. According to an interview with Yale Strom in 1984, the album sold 50,000 copies. Katz's comments in his autobiography say this about Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs and Brisses:

My second album for Capitol, and one that I love to this day, was also a big one. It was called Mickey Katz Plays Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses. (A bris is the circumcision ceremony.) The cover of this album is a delightful piece of artistic inspiration; it shows me, among other poses, sitting in a baby carriage, presumably after my own bris, smoking a cigar.

Other than that cover, this instrumental album had no comedy in it at all. If I do say so myself, it was simply delicious music. It was arranged by the late and great Nat Farber, who also played the piano in the orchestra for the album. Every note of the album breaths the flavor of the old but little-known happy Jewish music of the old country, yet all of the tunes are original. It's simply wonderful, joyus but poignant music composed, arranged and played by a lot of extremely fine musicians.

A number of the tracks had originally been put together for Mickey Katz's show Borsht Capades.

The players on most of the tracks are Mannie Klein (trumpet), Sy Zenter (trombone), Benny Gill (violin), Larry Breen (bass), Sam Weiss (drums), and Nat Farber (piano and arrangments). Additional players on some sessions included Morris Bercov (reeds), Ziggy Elman (trumpet), Bob Bain (guitar) and Lou Singer (xylophone). Two tracks were recorded in New York and the personnel remain unknown. Many of these tunes utilize a section or sections of various traditional tunes. The real star on this album is Nat Farber, whose arrangements are brought to life by the musicians. In Will Friedwald's liner-notes to the CD reissue he compares the arrangements to Fletcher Henderson's in the way the brass and reeds play off each other, and the construction of the band to the Ellington-Strayhorn ideal of starting with musicians rather than arrangements and songs:

In Katz's lifetime, many Jewish radio-station owners refused to play his records, in the same fashion that many middle-class black families looked down their noses at the blues. Even today, some of the more learned scholars, who proselytize for a monolithic concept of klezmer as sacred as the Torah itself, make the preposterous claim that “Katz was (merely) a novelty performer who enjoyed (only) a tenuous relationship to the Jewish world.” The statement has its parallel in John Hammond's claim that Duke Ellington ceased writing “authentic black music” after the ‘30’s.

…One of the great albums of the ‘50’s, Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs And Brisses brings to mind Tito Puente's equally great and no less popular Dance Mania in the way it universalizes what is essentially an ethnic music. By codifying their indigenous sounds for a large audience, both Katz and Puente not only avoid watering down their artistry, they actually elevate it.

Will Friedwald does a good job of raising the importance of Mickey Katz, though some of his individual comparisons can be troubling. Comparing the arrangements to Fletcher Henderson and the band construction to the Ellington-Strayhorn ideal is a valid point. Though to compare Mickey Katz to Tito Puente can be questionable. Tito Puente kept his Latin music in a dance style, whereas Mickey Katz brought his music into the theatrical setting. His show came out of the Vaudeville tradition with different acts, skits, and comedic songs. Any dancing that would accompany the music would be on the stage, not in the audience.

The selection here was chosen to highlight Nat Farber's arrangements. The melodic ideas could be found at many a Jewish simcha (party) in the 1950s. It is the performance that sets them apart.

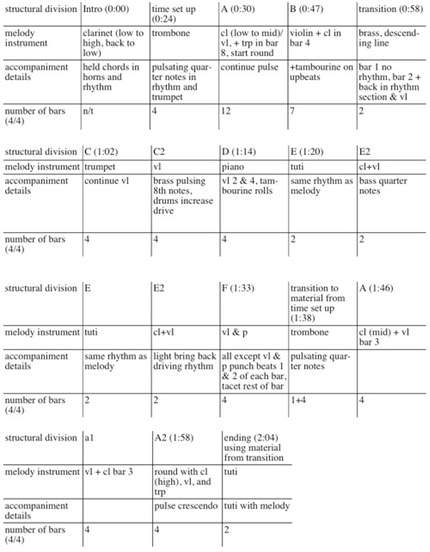

Mamaliege Dance (Farber-Katz) Quarter note = 166

One of the main features of the album is that nearly every musician gets a track that features him in a lead role, and “Mamaliege Dance” is not an exception. While the “Mamaliege Dance” opens with a clarinet Doina, the highlight of the track is not Mickey Katz's playing, but Nat Farber's arrangement. With “Mamaliege Dance”, Farber created a piece that suggests a ‘Jewish’ version of “Rhapsody in Blue”, in two minutes and eleven seconds! Overlapping lines feature instruments moving from playing harmony to melody and back again in the space of just a few bars. Register, especially in the clarinet, is important.

Figure 9: Form Chart “Mamaliege Dance”

This musical sophistication is packed into one of the shortest tracks on the album. The melodic material is primarily short jumpy phrases and while they sound “Jewish”, they do not evoke a dance tune. Nat Farber is creating something new with the “Mamaliege Dance”, something that evokes Romania but is placing it inside of the speed of business of America. Mamaliege is a hearty cornmeal porridge, and making it is a slow labor intensive process. If a person is called a mamaliege, it means they're sluggish and lacking energy. The “Mamaliege Dance” is the exact opposite, it has an energy that is non-stop.

This is one of only two tracks to have Ziggy Elman join Manny Klein playing trumpet, and the only one where Nat Farber plays a line that has the piano playing melody in front of the band. The piano solo may only be for sixteen beats, but against the lighter texture it stands out in the piece.

Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses will never been seen as being as successful as Katz’s comedic recordings, but is as important musically. Using Jewish material as the source rather than American pop tunes does not lessen the potential for parody. It also opens up the opportunities for Farber as the arranger to feature the instrumentalists for sections longer than sixteen bars. The parody is just as strong, and they still aimed at Yiddish-speaking insiders. Rather than having the primary subject being American culture, Jewish culture is the object of Katz’s wit.

Is the music Jewish? Is the music American? Is it successful in fusing the two styles together? Yes to all three. Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses brings together Jewish and American musical theatre traditions into a style where they are blend together to the extent that is is hard to tell where one style begins and the other ends.

Whereas the Tanz! and Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, and Brisses were recorded by musicians who primarily made their lasting musical mark playing and recording Jewish music, the next three musicians are known for working in other styles. These albums should be viewed as using Jewish music as a source material within the musical genre in which these musicians were established.

1963 was a benchmark year for the American Jewish music scene. Clarinetists Sammy Musiker and Naftule Brandwein both passed away, long past the height of their fame. On a positive note, two landmark Jewish-jazz fusion albums were released that year that showed two different approaches to playing Jewish melodies in a jazz style.

Recording jazz versions of Jewish songs or songs with a Hebraic flavor is a novel idea–and a good one.

My Son the Jazz Drummer!

In 1962, Allan Sherman released his debut album, my son, the folk singer. How much the title of Shelly Manne's My Son the Jazz Drummer! album was inspired by Sherman's album is up for debate, though the content of the two albums is extremely different.

Figure 10: Shelly Manne -“My Song the Jazz Drummer!” (cover)

Figure 11: Allan Sherman - “my son, the folk singer” (cover)

My Son the Jazz Drummer! was recorded December 17-20, 1962, at Contemporary’s studio, Los Angeles, California. Personnel; Shelly Manne, drums; Shorty Rodgers, flugelhorn & trumpet; Teddy Edwards, tenor saxophone; Victor Feldman, piano & vibes; Al Viola, guitar; Monty Budwig, bass. My Son the Jazz Drummer! placed Jewish melodies in a smooth West coast jazz setting. Not much is known about the recording of the album.

The liner notes were written by label head Lester Koenig. Koening takes a three pronged approach to discussing the album. First, he puts the album into a historical perspective, showing the long and varied history Jews have had with music, starting in the days of the Temple and going all the way to the popular songs written by Gershwin, Berlin, Kern, Rodgers, and Arlen. Following that are short biographies of the musicians to inform the reader why the musicians were suited to play this music. Koenig attempts to put the album within the Third Stream movement. The third and final section of the liner-notes are short descriptions of each track.

“Third Stream” was a term coined in 1957 in a speech by Gunther Schuller during a lecture at Brandeis University. It refers to music that combines elements of Western art music and ethnic or vernacular musics. Or, as stated in the Grove Dictionary of Music, where the article on Third Stream was written by Gunther Schuller: “At the heart of this concept is the notion that any music stands to profit from a confrontation with another; thus composers of Western art music can learn a great deal from the rhythmic vitality and swing of jazz, while jazz musicians can find new avenues of development in the large-scale forms and complex tonal systems of classical music”. As Lester Koenig states in his liner notes, “Shelly kept written arrangements to a minimum, using them as a frame and guide for free improvisation”.

My Son the Jazz Drummer! was reviewed in May of 1963 by Don DeMichael in Downbeat magazine and was given three out of five stars. Praise is given for the job that the label and Manne did performing this music in a tasteful way, and for Manne's drumming: “Special comment must be made about the excellence of Manne's drumming in the album; he remains one of the most imaginative and tasteful percussionists in jazz”.

Lester Koening's liner notes do a wonderful job of showing how the album was being presented to the listeners. As such, the liner notes are presented here before the analysis of the music.

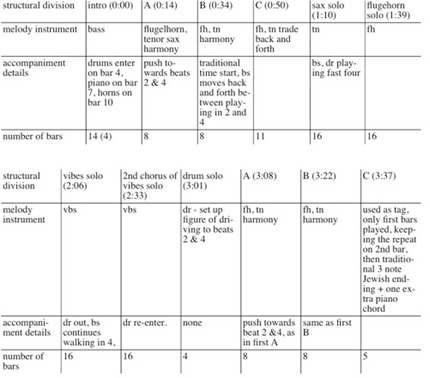

Hava Nagila (Come Let's Be Happy) (trad., arr. & adapted by Shorty Rodgers) half note = 115, 138

“Hava Nagila” was arranged by Shorty, who captured the gaiety of the original piece, an Israeli hora dance of rejoicing. The arranged melodic section ends with an accelerando, leading into driving solos by Teddy and Shorty (on flugelhorn). Victor's excellent piano comps for them, he switches to voices for a double solo with Monty and the excitement mounts as Shelly enters on their second chorus. A short drum solo leads the group back into the melody.

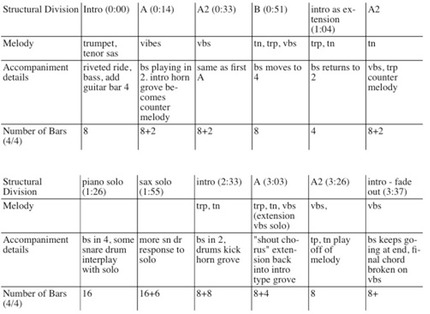

The track opens with an exotic sounding bass groove, joined in bar 4 by drums. One of the interesting rhythmic details of this groove is that the bass accents are almost all on off-beats until well into the melody. The drums, from when they come in, might not be playing time right away, but two and four are the accented beats. The way the melody is stated in the head by Shorty on flugelhorn and Teddy on tenor saxophone is interesting for its contrasts. The improvised solos are built over the sixteen bars of the A and B sections, the C section is only played once at the top of the tune.

Figure 12: Form Chart “Hava Nagila”

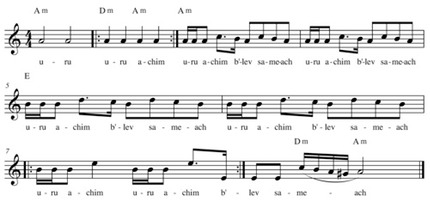

Three extensions are added in the C section to go from an eight bar phrase to the eleven bar phrase played here. As shown in the chart below, bars 2 and 7 are repeated. The repeated words, “Uru achim”, means ‘arise brethren’ or ‘awake brothers’.

Figure 1: C Part of Hava Nagila

The E pick up note in bar seven is only played on the repeat, with a different descending figure played in the final bar where the third extension is added. Also the accelerando mentioned in the liner notes happens during this section on the repeated quarter notes in bar two. This accelerando is standard performance practice when playing this tune.

The improvised solos are adequate, but nothing as inspired as the extension to the tune in the C section. Having the drums drop out for the first chorus of the vibes solo adds a nice textural change.

Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen (Jacobs - Secunda, arr. Lennie Neihaus) Quarter note = 134

“Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” is an interesting combination of Yiddish elements (the tune came out of New York's Second Avenue, home of the Yiddish theatre) and the blues feeling of contemporary soul-jazz. The arrangement is by Lennie Niehaus, who uses the soulful opening figure as an extension for the melody. Victor (on piano) and Teddy divide the solo chorus.

The arranger Lennie Niehaus, later famous for writing the scores to a number of jazz bio-pics and Clint Eastwood films, provides a film noir setting for “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen”. From its opening descending bass line and swinging riveted ride cymbal, the track breathes a dark and stormy night. Like with “Hava Nagila”, form is one of the ways to experiment with the tune. Where the improvised solo choruses are primilary straight thirty-two bar form, extensions are ever present in the head.

Figure 1: Form Chart “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen”

Starting with an eight bar intro the horns (trumpet and tenor sax) set up a lick that turns into the counter melody once the A section starts. Each of the two A's (eight bars each) have the melody played by Victor on vibes, and two bar extensions are tacked on to each one. The B section (eight bars) is played with the melody still in the vibes, and then the horn intro returns in the form of a four bar extension. This leads to the last A section, where the melody is now in the tenor and the vibes and trumpet play the counter melody line.

The first sixteen bars of the solo chorus are taken by Victor at the piano, the second sixteen are taken by Teddy on tenor with a six bar extension. Then an extended intro is played, twice though an eight bar idea. Victor returns to the vibes for the ending and plays more diads than he did in the opening statements of the melody. The track ends with two A sections, the first played in a shout chorus style, with a four bar extension that returns it to the laid back feeling. Then the second of the two A sections is followed by eight bars of the intro material as it fades out, and then the bass and vibes play an arpeggiated chord one after the other.

The description of how “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” is played comes across as very complicated, but in performances it is quite simple. The tune lends itself to what they are doing, and the fact that materials go from being in the foreground to the background and are used repeatedly give the track a great sense of continuity.

Yossel, Yossel (Steinberg - Casman) Quarter note = 127

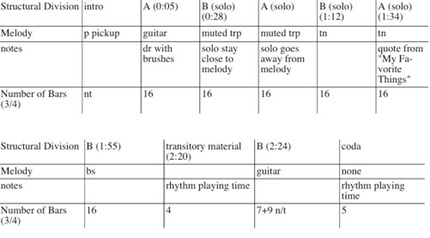

“Yossel, Yossel” is a Yiddish song which made the hit parade as "Joseph, Joseph" with English lyrics. There was no formaly arrangment. Shelly conceived it as a lament in 3/4 time with the guitar stating the melody. After beautiful solos by Shorty (muted trumpet) and Teddy, Monty Budwig is heard in a memorable bass solo.

“Yossel, Yossel” has a thirty-two bar form, that is AB. This form is advantageous to allow the solos to start after the guitar plays just sixteen bars of melody. The song is already one of yearning, a girl telling her romantic interest that she will wait for him. The muted trumpet solo does a wonderful job of carrying this theme. At one point in his tenor solo, Teddy quotes from John Coltrane's famous recording of “My Favorite Things”. Monty Budwig's bass solo is a half chorus, before the melody return in the guitar with the B section that was not played in the head.

Figure 15: Form Chart “Yossel, Yossel”

This track is a perfect example of why My Son the Jazz Drummer! works so well as a fusion album. It is just six musicians coming together to play a set of tunes which happened to be thematically linked by being Jewish. Then these Jewish tunes were played using pre-existing jazz ideas and conventions.

Was the album conceived to attract a larger audience than the normal Shelly Manne recording? It is hard to tell, as the liner notes end with “…and the end of a 41-minute program which leaves the listener wanting more. And there will be, for Shelly was at work on a second album of Jewish and Israeli music even before this one went to press”. The second album, if ever recorded has never been released. The CD reissue did have four bonus cuts that were single edits, so it appears that 45s singles were at least prepared if not released.

Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies in Jazztime

Figure 16: “Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies in Jazztime” (cover)

In January of 1963, Terry Gibbs and his band were playing Birdland opposite John Coltrane. Gibbs had recently formed a new quartet in New York after having spent the previous six years based on the west coast. In New York, Gibbs hired the bass player Herman Wright (with whom he had worked with in the 1950s), and the drummer Bobby Pike (on the recommendation of Mel Lewis). On the recommendation of Herman Wright, he auditioned and hired a female pianist from Detroit, Alice McLeod (1937-2007). It was while working with Terry Gibbs that McLeod met her future husband, John Coltrane.

The idea for the album of Jewish music in a jazz style was Gibbs’ and he brought it to Mercury Record's vice-president, A&R chief, and musical director Quincy Jones, who not only approved it, but also produced it. Gibbs wanted to do a straight ahead jazz album in the same way that many Latin jazz albums of the time period were recorded. Instead of the clave played by congos and claves, the second drummer would play Jewish patterns under the music. For the Jewish side of the band, Gibbs hired his brother Sol Gage to get some of the best club-date musicians in New York. The musicians Gage hired were the clarinetist Ray Musiker, trombonist Sam Kutcher, and pianist Alan Logan. These were musicians so in tune with the Jewish music that Terry only had to give them printed music for his two original tunes.

The format of the album was somewhat unique, as it featured two side by side, mostly independent quartets. Unlike albums such as Rich Versus Roach (where two leaders brought their ensembles together to play the head sections together and trade solos), for the most part Jewish Melodies in Jazztime has the Jewish band playing the heads and tails and the jazz band playing the solos in-between. This A-B-A format of the A sections being “Jewish” and the B sections being jazz dates back to at least 1938 when Benny Goodman sideman Harry Finkelman (a.k.a. Ziggy Elman) recorded “Freilach in Swing” among his sides as a band leader for Bluebird.

The session must have been quite a party; Quincy Jones showed up in a yarmulke (skullcap) and tallis (ritual prayer shawl) and the composer Lalo Schifrin dropped in and brought a box of matzoh. The album is an early three track stereo mix (there was also a monophonic version), and everything is hard panned to one channel. On the right channel are Alice McLeod, piano (jazz); Sol Gage, drums (Jewish); Sam Kutcher, trombone (Jewish); Ray Musiker, clarinet (Jewish). On the left channel are: Herman Wright, bass; Bobby Pike, drums (jazz); Alan Logan, piano (Jewish). And in the center channel: Terry Gibbs, vibes. Herman Wright, the only bass player, comes from the jazz side, but is called upon to also play with the Jewish ensemble. There is some bleed through, especially from right to left, with the trombone and clarinet, though this could be room reflection noise. As it was an early stereo Hi-Fi recording, an equipment list of microphones and tape equipment is given. The album was recorded at A&R Studios on January 11 and 12, 1963.

The album was reviewed in Downbeat in October of 1963 and given three and a half stars by Don Nelson. He describes the Jewish band as having a catering-hall sound, and that the clarinet and trombone produce a quasi-Dixieland sound that contrasts with the more modern sonority of the Gibbs quartet. Mr. Nelson says the honor for best solos go to Alice McLeod and that the extra half star is largely for her performance, both soloing and comping.

For this study I have chosen to look at three tracks: two Yiddish tunes that crossed over to the American Pop charts and one of the two new tunes that Terry Gibbs wrote for the album.

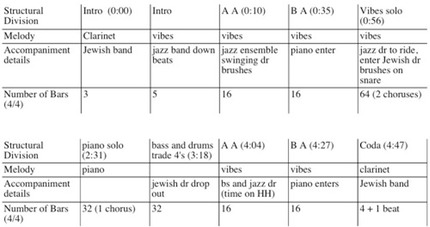

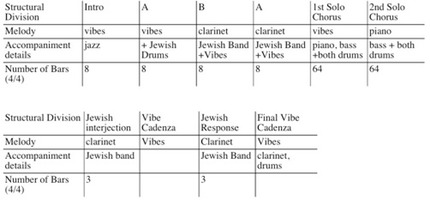

Bei Mir Bist Du Schon (Jacobs - Secunda - Cahn - Chaplin) Quarter note = 160

Figure 17: For Chart "Bei Mir Bist Du Schon"

This track sets up the entire album, not only in the overall form of each track, but also in the form that the solos take. Gibbs’ solos are much more melodic and tuneful whereas McLeod’s solos are much more linear modal lines. In fact Gibbs’ vibe solo keeps hinting at the tune “All of Me” by Seymour Simons and Gerald Marks, and even has another quote in the second chorus at the beginning of the last A.

Alice actually stole that date from me. She was starting to play runs she got from listening to John and all the musicians flipped out every time she played. She was making those Eastern-style runs on the minor songs and they sounded very authentic. I was the Jew and she was wiping me out.

The interlocking drum groove of jazz and Jewish rhythms from the solo section comes back a number of times over the course of the rest of the album.

Figure 18: Drum transcription

Bobby Pike, playing from the jazz side, is swinging the ride cymbal pattern. This is overlaid against Sol Gage playing a very typical Jewish pattern in a non-traditional way, with the use of brushes. The natural jazz accents are on beats two and four, though Boobby Pike plays his ride cymbal pattern with no accents and his hi-hat is not audible in the mix. Any confluence of the accent in the Jewish part on beat four is taken away by the immediate drive toward beat one. On paper the combination of the two seems a bit odd, as the emphasized parts of the measures interlock like a zipper missing some teeth. In performance it works, though at times it is a bit monotonous, lacking in dynamic and textural change.

And The Angels Sing (Ziggy Elman - Johnny Mercer) Quarter note = 140

The albums second side opens with the original Jewish-jazz fusion tune, “Der Shtiller Bulgar”, under its most famous name, “And The Angels Sing”. This piece cannot help but make the listener think of Lionel Hampton and Benny Goodman, and Gibbs wisely does not try to avoid these comparisons. The first chorus is straight melody, while the second chorus is a vibe solo. It is a vibes solo that looks to the father of the jazz vibes, Lionel Hampton, for inspiration. During the B section of the solo, Gibbs even references Hanmpton’s signature tune “Flying Home”. At the end of the vibes solo, Gibbs goes back and plays the first part of the A, the Jewish band comes in with the Ziggy Elman double time feel before the jazz side comes back in to handle the ending.

Figure 19: Form Chart “And The Angels Sing”

S & S (Terry Gibbs) Quarter note = 160

The first of two original tunes, “S & S” starts out sounding like the average minor blues number, until bar nine, when Sol Gage comes in with the Jewish rhythm played with brushes. The other unique feature of this track is that the solo choruses are even in length, rather than the piano being half as long as the vibes.

Figure 1: Form Chart “S & S”

The melody to S & S is a two section bulgar. The A section is at its core two quarter notes followed by two pairs of eight-note triplets. The B section is of a contrasting nature, still very Jewish, but eighth-note based without triplets. Combined this gives “S & S” an American-Jewish flavor. It would sound weird if a Jewish band were to play it as a dance tune, though all the elements are there. It is all eight bar repeated phrases in 2/4. It is a very square, danceable tune, though the tempo is a bit fast for a dance floor. Terry Gibbs gives what Jewish players would describe as a very schmaltzy performance, with lots of grace notes or, as the Jewish would describe them, deydlakh. In this case all the quarter notes are played with, as a percussionist would describe them, flams, that is, a preparatory softer note played with the opposite hand on the same pitch. The jazz solos have nothing to do with the Jewish section of the tune; their only connection to the Jewish music is the pattern Sol Gage is playing with brushes on the snare drum. The back and forth nature of the melody and cadenzas at the end tie the entire track together.

Of the albums in this study, Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies in Jazztime was the last to be recorded. How does it compare to the recordings that preceded it? Gibbs shows wider musical breadth than the Shelly Manne recording, as well as innovative new tunes just as powerful as the ones written by Sammy Musiker for Tanz! Musically Gibbs was very successful, blending old and new styles in jazz soloing and orchestration. Like the other albums in this study, it does not appear to have been commercially successful, and Gibbs never recorded another album of Jewish sourced tunes.

While all five of these albums might have struggled to find an audience when first released, in the long term, they were very successful in influencing later generations of players. These five albums reveal a creative period in post-war Jewish music that for too long has been neglected by scholars and popular writers.

Footnotes

- Terry Gibbs with Cary Ginell. Good Vibes; A Life in Jazz (Lanham, Maryland; Scarecrow Press, 2003), p. 40.

- Irving Fields, Personal communication with the author, April 21, 2004.

- Josh Kun, liner notes to Irving Fields Trio Bagels and Bongos 2005 Reboot Stereophonic reissue B0004859-12.

- http://www.rebooters.net/rebootstereophonic/rsgeneral.html viewed on June, 26, 2007.

- Apollo LP491, undated.

- Riverside RLP 7510, 1961.

- As a side note, one of the many people to record a cover version tune was Carlos Santana on his 1981 album Zebop!

- The spelling of the Yiddish lyrics reflect the 1934 original edition published by Henry Lefkowitch, original sheet music in author’s collection.

- It is unclear if this is a cowbell, as there is also a scraping sound. It may be a metal guiro.

- Personal not listed on Original release, comes from 2002 reissue.

- Ivan Fiedel, Tanz! Epic LN 3219. 1955. Liner notes.

- Composed by Abraham Ellstein, the original recording featured Seymour Rechtzeit and the Barry Sisters.

- "Papirosen" is the song of a young boy trying to sell cigarettes in a rain storm while talking about all of the calamities that have afflicted his family.

- There was a long tradition in the weddings in Eastern Europe (which would last multiple days) to have music for listening. With the shorter time span of weddings in America the only genre of the music for listening that survived was the Doyne.

- Mickey Katz and Hannibal Coons. Papa, Play for Me: The Hilarious, Heartwarming Autobiography of Comedian and Bandleader Mickey Katz. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1977, pp 130, 133-137.

- Strom 2002, p 182.

- Katz 1977, p 100.

- Friedwald, Will. liner note, Simcha Time, Mickey Katz Plays Music for Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs & Brisses. (The Klezmer Sessions). World Pacific CDP 7243 8 30453 2 7. 1994.

- Ibid.

- Katz 1977, p. 112. Talks about playing run of Borsht Capades in Chicago and not having his musicians that he had used when the show was in Los Angeles; Manny Klein, Ziggy Elman, and the stage freight that he developed because of this.

- Marks, Gil. The World of Jewish Cooking: more than 500 traditional recipes from Alsace to Yemen. New York, Fireside Press, 1999, p. 192.

- Don DeMichael. "Shelly Manne My Son the Jazz Drummer." (Review) Downbeat, XXX/10 (May 9th, 1963).

- The Shelly Manne archives are held by the Percussion Arts Society (www.pas.org) and at the time of this study where being moved from Oklahoma to Indiana.

- Koenig, Lester. “My Song the Jazz Drummer” liner notes.

- Third Stream was originally used to describe the meeting of Jazz and Classical music, it is not its own type of music. In the case study to follow, it is jazz meeting vernacular Jewish music.

The description from a 1981 New England Conservatory brochure reprinted in Gunther Schuller's 1986 collection Musings; The Musical Worlds of Gunther Schuller says this; “It is a non-traditional music music which exemplifies cultural pluralism and personal freedom. It is or those who have something to say creatively/musically but who do not necessarily fit the predetermined molds into which our culture always wishes to press us. Third Stream, more than any other concept of music, allows those individuals who, by accident of birth or station, reflect a diversified cultural background, to express themselves in uniquely personal ways.” It then goes on to list things that Third Stream is not.

- Schuller, Gunther: ‘Third Stream’ Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 20 June 2007).

- Lester Koenig. liner notes My Son The Jazz Drummer! Contemporary S7609. 1963.

- DeMichael, Don. “Shelly Manne My Son The Jazz Drummer!” (Review) Downbeat, XXX/10 (May 9th, 1963).

- Ibid.

- Koening, 1963.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John Coltrane, "My Favorite Things." Atlantic Records, 1961.

- Koening, 1963.

- The four bonus tracks are; “Zamar Nodad”, “Exodus”, “Tzena”, and “Hava Nagila”.

- Gibbs 2003, 227-230.

- Ibid, 229.

- Ibid, 229.

- Polygram Records 1959.

- Gibbs 2003, 229.

- Nelson, Don. “Terry Gibbs Jewish Melodies in Jazztime”. (Review). Downbeat XXX/27 (Oct 10, 1963).

- Gibbs 2003, 229.

- Transcription by the author.