The core of the musical repertoire considered ‘Klezmer’ today is only a small segment of what all Jewish musicians were once required to play. Along with the changing repertoire, this overview takes special note of the changing instrumentation over the past three centuries. The history of Ashkenazi instrumental music has been outlined in Seth Rogovoy's 2000 book The Essential Klezmer, and Walter Zev Feldman’s lecture at KlezKanada in 2001.[1] This outline divides the music history of Ashkenazi Jewery into five groupings:

1)Biblical to Middle Ages

2)European

3)American

a)End of the 19th century until World War II

b)Post War

4)Revival

5)Renaissance

It is important to note that this overview only applies to Ashkenazi Jews whose roots are within within the Pale of Settlement (Galicia [Poland], Lithuania, Ukraine, Western Russian provinces) and Romania. Ashkenazi Jews living within Germany and further west developed different and unique musical forms. Before turning to the American post-war years which will be the prime focus of this study, background on the first two periods is offered.

Biblical to Middle Ages

Before one can look at the musical output in Jewish society one must look at the tortured relationship that music and musicians have had with it dating back to Biblical times. Musicians have held a unique place in the strata of society with their all-important role and insecure underclass status.

Music was once an integral part of the Jewish religious experience, from the book of Exodus and the crossing of the Red Sea where we read of Miriam dancing with her timbrals, to the orchestra of the Temple where the list of instruments included harps, lyres, oboes and cymbals.[2] While we have names of instruments, and some idea what they looked like, we have very little idea what they sounded like. A few of the instruments may have survived— in both the Sephardic, and especially the isolated North African and Yemenite Jewish women's vocal tradition it is common to find the use of a frame drum to accompany singers.[3] The Ashkenazic women's vocal tradition is much more recent, and is an unaccompanied tradition.

Since the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, rabbinical authorities have placed various restrictions on the playing of music. The rabbinical restrictions banishing instruments can be found in the Book of Lamentations 5:14: “The elders have ceased from the gate, the young men from their music.” There are still communities that to this day follow the strictest interpretations of this verse and ban all instrumental music, and a few that only allow hand drums to accompany singing.

Maimonides (Rabbi Moses ben Maimon), a philosopher and physician who lived and worked in Spain during a flourishing time of Jewish philosophy in the Middle Ages, wrote this six point responsa to a question about listening to regional Arabic music (singing accompanied by reedpipe) prohibiting:

1. Listening to a song with a secular text, whether it be in Hebrew or Arabic

2. Listening to a song accompanied by an instrument

3. Listening to a song whose content includes obscene language

4. Listening to a string instrument

5. Listening to passages played on such instruments while drinking wine

6. Listening to the singing and playing of a woman[4]

This six-point summary of prohibitions on music is in ascending order of severity. To this day many of them are still observed in the Orthodox and Hasidic communities. What is interesting is the fact that these restrictions have nothing to do with the ban on religious music, they only ban secular music. Over the years, rabbinical authorities used the responsa literature on secular music, especially Maimonides’, and expanded it to regulate and restrict Jewish music within the context of Jewish celebrations.

Instrumental music has, as such, been moved to the "un-Jewish" profane world. The privileging by the talmud of a tradition of male-sung, sacred text based religious vocal music, with instrumental accompaniment, has had a profound impact over the years on the descriptions of music that have gotten passed down to study.[5] For centuries what we have had are edicts from both Christians and Jews banning the study and performance of each other’s music.[6]

European

The earliest histories we have of instrumental Jewish music in Eastern Europe do not come in the form of composed music, or even insider or outsider descriptions of the music they are playing. The earliest histories come to us in the form of guild records, describing what instruments the Jews were allowed to play, how many musicians could play, and when they were allowed to play.[7] Many towns limited the Jews to quiet instruments such as fiddles, flutes, and tsimbls (chromatic hammer dulcimer), and would ban loud instruments such as brass and drums. Woodcuts from the eighteenth century show most ensembles with three to five musicians, most playing string instruments.[8] The fiddle was the quintessential Jewish instrument until the clarinet overshadowed it with musicians returning from military service in the later half of the nineteenth century.

Photographs starting in the later half of the nineteenth century give excellent evidence for the instruments being played, and in some cases who was playing them.[9] Traditionally in Eastern Europe, the poyk (drum), would have been played in most cases by a young boy, who may or may not have been paid at the end of the job. Beregovski writes of Avram-Yehoshua Makonovetskii, a fiddler and bandleader, responding to his questionnaire, that the pay scale in many places was a half share for the drummer.[10]

Performance Venues and Musical Genres

The repertoire of music they played was diverse without being eclectic, including Jewish and non-Jewish tunes for both dancing and listening.[11] Up until the middle of the nineteenth century Jews were not allowed to enroll in music conservatories, so they tended to come from musical families and were taught within their own family, and at times were apprenticed to other musical families.[12] Even though Jews did not go to music schools, many learned to read music, which allowed them to stay current and play the popular, cosmopolitan European repertoire of the day. This was important outside of major cities, where they would routinely be called to perform for the landowners.

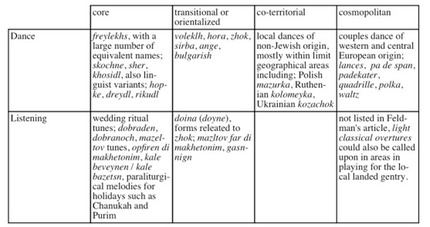

The primary performance venue for these musicians was the Jewish wedding, and as such the history of Jewish musicians is closely tied up with that of the wedding jester or Badkhan. In some places they were the only professional musicians, and could also be found playing for non-Jews.[13] While their repertoire varied greatly by location, studies have been able to break down the different types of music that made up the repertoire. Walter Zev Feldman has broken down the classification of types of tunes into four categories, presented in the following chart. [14]Following the chart some of the more important genres will be discussed. Ratios of music played in each category would change depending on for whom music was being played.

Figure 1: Instrumental repertoire categories chart

In America these categories stay the same, even if the musical content in them changed over time. Examples of American co-territorial dance genres include cha-cha, rhumba, samba, twist, etc.[15] Co-territorial music is the musical genres of other ethnic groups played within geographical areas where both groups are living.

The major difference between the freylekhs and its equivalent core dances is primarily found in the choreography of the dance and not in the music, though tempi do differ.[16] It is important to remember that most of the music being discussed here is for dancing, and that the music is ancillary to the dance. Many of the musical forms are governed by the choreography of the dance that they accompany. This overview attempts to point out both important musical and choreographic differences in the forms discussed.

Feldman documents the transformation of the bulgarish/bulgar into the dominant Jewish dance. The bulgar entered the Jewish repertoire through Bessarabia where it appears to have been encountered by Bessarabian Jewish and Gypsy musicians performing in Istanbul.[17] The bulgarish/bulgar began to supplant the freylekhs as the dominant Jewish dance in much of Eastern Europe in the early twentieth century. And in America, the bulgar was brought to the forefront by the compositions and performances of Podolian born clarinetist Dave Tarras, who will be discussed in more depth in the coming sections.[18]

Jewish music can be distinguished from the surrounding Balkan genres in its extremely limited use of the triplet. The freylkekhs is a duple-based circle dance, whereas the bulgar is a triplet-based dance form that comes in two variations. A couples bulgar is either done in a square of four, or in lines with men on one side and women on the other. The better known variation today is a 6 beat circle dance pattern that was previously alien to Ashkenazi dance. Both versions of the bulgar, though especially the circle variant, are young men's dances that offer them lots of places to shine or show off their dancing skills. Shining is a traditional feature of Yiddish dance, be it the leading out portion of the sher, or the dancing in front of the bride and groom. The basic steps of the bulgar have survived in popular Jewish dance as the Israeli Hora, though danced in the opposite direction starting left.[19] The connection between the Israeli Hora and the transitional hora is one of name only. Hora is ancient Greek for dance, and variants on the word can be found describing dance throughout the region. In the Yiddish dance context, it can most often be found used synonymously with zhok, a slow tempo circle dance in 3/8 time.

Many of the listening styles did not survive the abbreviated wedding celebration that developed in America, where week-long wedding celebrations were no longer practical. The doyne, however, not only survived, but prospered as a feature for the clarinetist to show off his playing skills. The doyne is a genre of Romanian shepherd tunes, of which the Jews only play one form. The doyne had superseded the taksim as the improvisational genre of choice in the 1860s after the Romanians took over political control of their own cities.

The research on the issue of transmission of genres from one culture to another is just at its beginning. What this transmission has to say about how musicians draw on the popular music of other contemporary cultures is crucial to our understanding of how American born musicians fused contemporary, co-territorial “American” genres with Yiddish instrumental music after Word War II.

Enlightenment

In the Enlightenment period, the use of music in every-day life grew in both Jewish and non-Jewish communities. Within the Jewish community the expanding role of music is seen most profoundly within the counter-culture where music is seen as being able to raise one's spirituality to a higher level. It was within this community that the word kle-zemer (lit. vessels of song) from Kings 11, chapter 3, verse 15, came into use as a term denoting the musicians or Klezmorim. The status of the musician in this community was also elevated in how they interpreted this line from 2 King 3:25:

Now then, get me a musician. As the musician played, the hand of the Lord was upon him.

This community was centered around specific Rebbes who were the leaders of courts, many of whom included both court composers and musicians. Wordless melodies, nigunim, of some of these courts have survived to this day and are held in the same high regard as any other preserved connection to the history of the court.

Today the counter-culture has turned into the old guard and one of the standard-bearers of the community. We know them as the Hasidim. While they are still concerned with the separation of the holy and profane, they understand the impact that music can have on people, and were willing to bring instrumental (and vocal) music into their community as long as it was used for holy purposes.[20]

Silence is Better than Speech

But Song is Better than Silence

—Hasidic Saying[21]

While the overall attitude toward music comes out of mystical Jewish traditions, different Hasidic courts traditionally tend to prefer different music. Our knowledge of how each court's music differed from the others in Eastern Europe is unfortunately limited by Rabbinical edicts banning the transcription of melodies, of both secular and religious origins, that were used religiously.[22] The reason for these bans was that the Rabbis did not want the music that was being used for religious purposes to be easily available where non-Jews, or even other Jews would be able to use it for secular purposes. After World War II, when most Hasidic courts in Europe were destroyed, the courts that were able to be reconstituted in America were much more open to preserving their musical heritage. Rabbi Yankel Talmud, the composer for the Ger Hasidim, published Malchin L'bes Gur (Composer to the Court of Ger), and the Chabad Hasidim had Rabbi Samuel Zalmanoff direct the publication of Sefer Hanigunim. An even wider range of courts had audio recordings made, either with their own singers, or professional singers. American audio recordings of the nigunim of Bobov, Modzitz Ger, Vishnitz, and Chabad-Lubavitch give us a window into what the music was like in Europe. The situation is further complicated by the fact that these are commercial recordings with instrumental accompaniment added to what for the most part was originally an a cappella tradition.

Through this window we are still able to draw some broad conclusions about the musical diversity once seen in the different Hassidic communities.[23] The Rebbes of Modzitz were big fans of waltzes, not for dancing but for singing.[24] The tunes of Ger are similar to the popular peasant dances of the surrounding area in Poland.[25] The Modzitzer Rebbes were extremely prolific in the numbers of tunes they wrote, and at the same time in the length of tunes.[26] While there are short Modzitzer tunes, many are long, multi-sectioned pieces with multiple themes, some of which take up to a half hour to sing. They are described as being “art songs” compared to the average Hasidic tune being of folksong length. Rabbi Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev wrote prayers in the vernacular Yiddish so that the average person could fully understand them.[27] Some of Reb Yitzchok's most famous tunes are still in the popular repertoire of Yiddish songs. In Chabad-Lubavitch, music is seen as having a more mystical quality. Chabad teachings say that what is impossible to express in words, may be expressed though music.[28] By the meditation to a tune through singing, one may climb a series of steps toward high states of divine bliss.

2. Peter Gradenwitz, The Music of Israel: From the Biblical Era to Modern Times; 2d ed. (Portland, OR; Amadeus Press, 1996) p. 45 & 61.

5. Idelsohn, Abraham Z. Jewish Music: Its Historical Development (New York: Henry Hold, 1929; reprints New York: Shocken Books 1967 and Dover 1992) p. 18.

8. Moshe Beregovski, Jewish Instrumental Folk Music; ed. and trans. Mark Slobin, Robert Rothstein, and Michael Alpert. Annotations by Michael Alpert (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press 2001). Walter Zev Feldman, “Bulgӑreascӑ/Bulgarish/Bulgar; The Transformation of a Klezmer Dance Genre” in American Klezmer: Its Roots and Offshoots. Mark Slobin, ed. (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002) originally published in Ethnomusicology 38:1 (Winter 1994), p 91; “Written and visual documents from the first half of the seventeenth century onward show a preference among Jewish musicians for ensembles of fairly fixed character, usually featuring one or two fiddles, a bass and a cymbal (the portable hammer dulcimer), and sometimes also a flute”.

9. Beregovski 2001, Sapoznik 1999 and Yale Strom, The Book of Klezmer; The History, The Music, The Folklore (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2002) include a number of photographs of European Ensembles.

12. Hankus Netsky, “Klezmer: Music and Community in 20th Century Jewish Philadelphia” (Ph.D. dissertation, Weselyan University, Middletown, CT, 2004), pp. 38-39; Rubin, Joel Edward. “The Art of the Klezmer; Improvisation and Ornamentation in the Commercial Recording of New York Clarinettists Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras 1922-1929” (Ph.D. thesis, City University, London, 2001), pp. 65-66.

15. See Netsky 2004, pp 95-102. for a discussion of dances that entered the Philadelphia market in the first decades after World War II and the changing ratios of Jewish and American music on the bandstand.

16. An example of how the musicians saw these as being related even if the tempo varied is shown in how Ben Bazyler a Warsaw area musician describe the khosidl as a pameylekher (slow) freylekhs. p. 76 In Michael Alpert, “All My Life A Musician; Ben Bazyler, a European Klezmer in America.” in American Klezmer: Its Roots and Offshoots. Mark Slobin, ed. (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002).

20. There is actually some evidence that this was the case dating back far earlier, but it is only with the Hasidim that it comes out into the open.

22. Velvel Pasternak, Beyond Hava Nagila a symphony of Hasidic Music in 3 movements; (Owings Mills, MD: Tara Publications 1999). pp. 75, 112.

23. Similar diversity was also seen in the Instrumental music of non-Hasidic communities in Eastern Europe, and even in America Jews from different towns would want to hear their music. This diversity loss is one of the main details that separates the “Klezmer” Revival from the earlier time periods.